Watch the Video

The Atari ST is a machine which emerged in 1985 and immediately went head to head with the Amiga 1000. The Atari ST is known for Games, music, desktop publishing and in a lot of cases, being a poorer version of the Amiga, but that’s not always the case, and to begin with the ST outsold the Amiga.

Subscribe to Nostalgia Nerd on Youtube

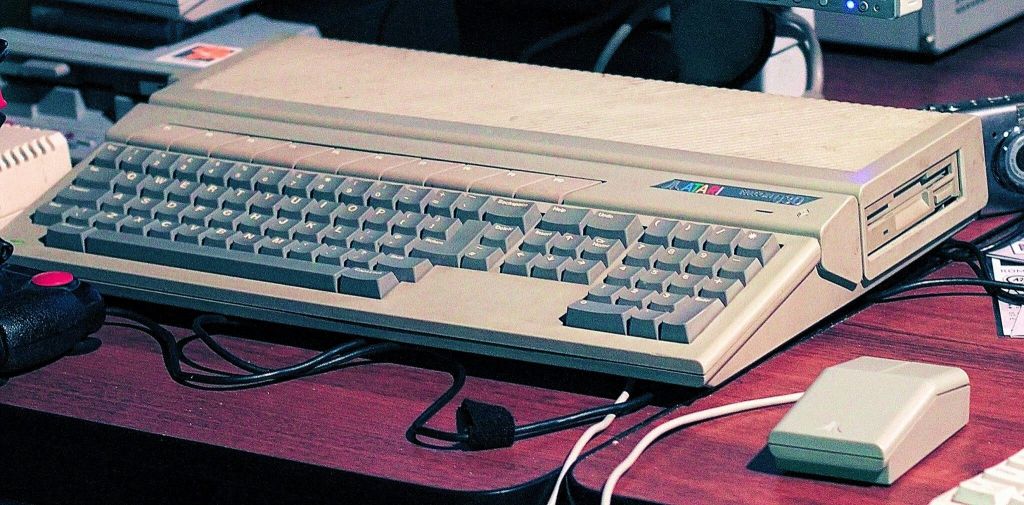

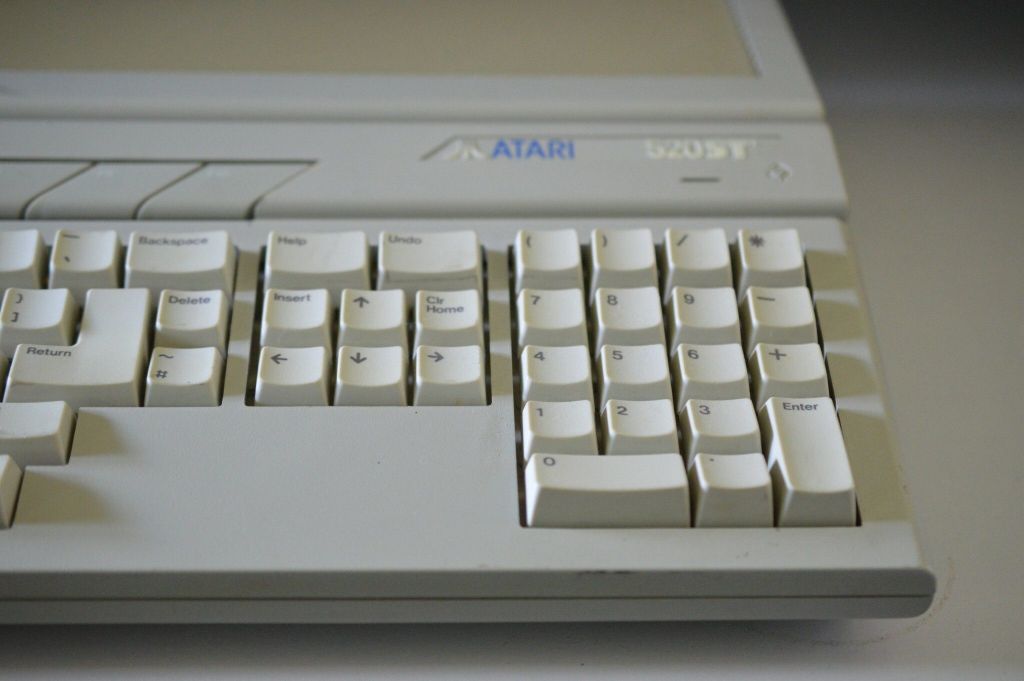

I’ve covered several computers close to my heart already, including The Sinclair Spectrum and the Commodore 64. These were both machines I owned, during the 80s and early 90s, but it wasn’t until the Christmas of 1994, that I obtained what I considered a real home computer. For me a real computer needed a few things… the first was a numeric keypad.. the 64 and Speccy were grand machines, but they felt toy like without this additional wedge of keys tagged onto the side. These keys allowed me to calculate lightning fast arithmetic, and I’m sure were the only reason I obtained a maths GCSE. Second was a graphical user interface. Sure you could get these for the Speccy & C64, but GEM Desktop was usable, it was useful, it was built into ROM and most importantly of all, there was a mouse, which is handily my third item. Last, on the list was a loading method which didn’t take half a day, which was reliable enough for the media to be slung around the house and produced a satisfying click sound on a whim’s notice. I cannot think of a more favourable storage medium than 3.5″ floppies. Even to this day, the feel, the labelling, the write protect notches, the volatility, the noises… Mmmmmmmm, damn, it’s just so good.

Now although Christmas ’94 was when I became an official owner of an Atari 520STFM (we’ll come back to the labelling in a bit), it wasn’t the first time I’d used one. My friend Michael and I would while away post school afternoons playing through Gauntlet, Ghouls & Ghosts, Outrun, Overdrive and anything else which came in the Atari Powerpack, until he upgraded to a fully fledged PC and I became the proud owner of his old machine.

So, you can see why I have quite an attachment to this fine piece of 16 bit hardware. In fact, I still have the exact same machine to this day. It needed a new power supply a few years ago, but other than that, it’s works as good as the day she was bought.

Now, the story of the ST is an interesting one. It involves Atari’s rival, Commodore and it begins way back in 1984. Grab some popcorn kids.

Back in 1983 Jack Tramiel was running Commodore International through an aggressive price war with Texas instruments, forcing Texas to exit the home micro market. The only problem was this also impacted Commodore’s profits leading to disagreements amongst the Commodore board. These disagreements led to Jack leaving the company. He then went on to form Tramel Technology with his sons and some other Commodore staff, including Shiraz Shivij who had helped build the Commodore 64 and would be instrumental in the design of Tramel’s next machine. After originally seeding an idea for a low cost 16 bit computer at Commodore, Jack & his team now put this idea into motion. Originally the company considered using a 32 bit National Semiconductor NS32000 CPU, but was left unimpressed by it’s performance and cost, so started to investigate Motorola’s 68000 chip.

It was around this time that Atari inc. was coming into a bit of trouble. Jay Miner had previously approached Atari to seek funding for his Amiga chipset, with a licensing deal in motion which would have led to Atari selling Amiga machines, but following the video game crash of 1983, Atari’s parent company, Warner Communications were getting a bit anxious about the whole situation, especially as Atari were losing $10k a day, and were looking to cut the company adrift. Jack was prompt to notice this opportunity and in July 1984 injected $30m into Atari and acquired it’s consumer division for $50 cash and $240m in promissory notes and stocks, giving Warner a 20% stake in the newly named Atari Corporation. Tramel Technology was then swept into this new branding.

Meanwhile Commodore had been left floating with no direct path to a next generation computer. Amiga still had debt to Atari, and had approached Commodore for funding. Immediately seeing a path to release their own machine, Commodore stepped up and paid off Amiga’s $500,000 dollar debt to Atari, believing this would void any licensing contract between Amiga and Atari, whilst also buying out the fledgling technology company for $24 million. This ultimately suited Tramiel as he could continue developing his own machine and avoid investing another $20m in Amiga to finish their custom chips, but as Commodore had tried to sue Tramiel for taking most of their employees, Tramiel decided to sue Commodore back for damages and prevent them from using the Amiga technology. This led to some legal action which delayed Commodore’s production – whilst also buying Atari some time – which was finally settled out of court in 1987. Ultimately this all led to the rather back-to-front situation of Commodore owning Atari’s old investment – The Amiga, and Atari starting development of what would have been Commodore’s 16 bit machine, under Jack Tramiel’s team.

You can peer into an alternate version of these events in my What if Amiga didn’t exist video.

Tramiel used Atari’s remaining stock of console inventory to keep the company afloat while they worked the new machine. The key ideas of having a 16 or 32 bit architecture with strong music and graphic support were core to the machine’s design and with Shiraz Shivji in charge of hardware the team got to work around the clock to deliver a machine quick enough before the money ran out. The entire future of Atari Corporation was riding on what would emerge. The project was code named RBP, standing for “Rock Bottom Price” and the mission statement was to produce a “cheap yet powerful home computer”. Jack wanted something that would smash the Apple MAC and IBM PC out of the water, but at a much lower price point. To this end, Motorola proved even more essential as in addition to the CPU, they had a number of unsold parts, which failed to meet specification. Atari realised that by tweaking their design, those parts could be used in the new machine saving both companies millions of dollars. For sound, a custom AMY processor was planned, but with time running out, the Yamaha YM2149 chip was utilised. But as the team weren’t totally happy with the chip’s capabilities, it was decided that an external music interface should be built in from the go. Again using cheap Motorola serial chips, the MIDI ports cost just 75 cents to implement. A brilliant piece of foresight that would stand in good stead for the years ahead.

The last element required was essential in competing with Apple. Microsoft had contacted Atari early in development to suggest porting Windows over to the new machine, but it was rejected as Windows was still 2 years from being completed. This didn’t tie in with the short timescale Atari were seeking. The only solution was with Digital Research and to licence the GEM desktop from Gary Kildall. A team of Atari engineers were dispatched to work with Digital Research and a GEM port was delivered in a remarkably short time, with bugs still being ironed out during the actual hardware porting. GEM was layered to work with the underlying GEMDOS based operating system; TOS (speculated to stand for The Operating System, or Tari Operating System but usually associated with Tramiel Operating System), initially the OS was loaded from floppy, but machines were provided with ROM sockets to upgrade to a ROM based TOS. Later machines would have TOS & GEM Desktop built into ROM as standard. Over at the competitor’s table, Commodore sought a specialist UK team to create their ROM based Amiga operating system, Kickstart, and User Interface, Workbench, which was always supplied on separate floppies.

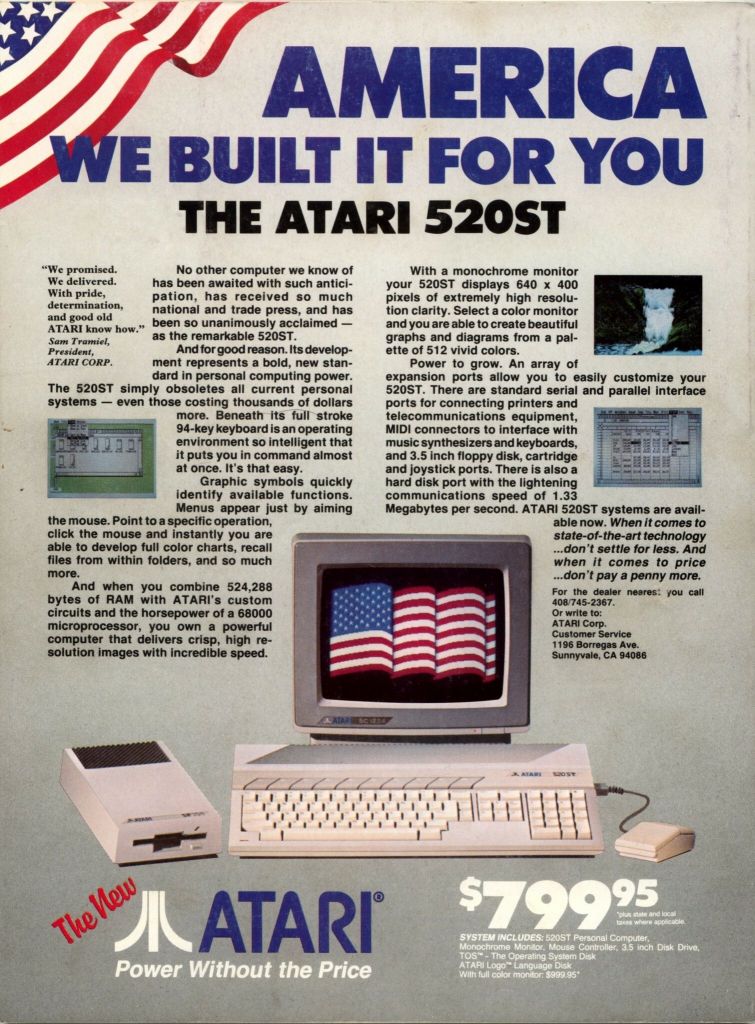

With everything in place, the machine was developed in just 5 months and named the 520ST due to the 520kb memory and the 68000 chip having a sixteen bit external data path, but thirty two bit internal architecture. Atari also considered releasing 128k and 256k versions named the 130ST and 260ST, but it was decided there would be too little free memory with the OS loaded into RAM.

During the January Consumer Electronics Show in 1985, almost complete versions of the ST were showcased (these were in fact 130ST models) and the industry was instantly impressed with the offering, whilst noting the corner cutting similarities between the prototypes & Jack’s earlier machine, the Commodore 64. The Commodore Amiga was also demonstrated at this show, but Atari pipped them to the post and soon after in May the first 520ST machines went on sale. The corner cutting look was gone and production machines looked more professional and quickly nicknamed “Jackintoshes” due to abilities which seemed to spill all over Apple’s current market. They were also the first true 16 bit home computers.

Even though Amiga had a 2 year head start on development, Atari had pushed their ground breaking machine out over a month ahead of Commodore’s product and with the cheaper price point of $799 with monochrome monitor and $999 for colour, compared to Amiga’s $1,295 with an additional $300 on top for a colour monitor, Atari initially gained the upper hand. And even though the ST lacked the custom Amiga chips found in the 1000, it still had a few tricks up it’s sleeve, which made the $799 price point even more attractive.

The first was a flicker free high resolution mode offering 640×400 pixels, and was incidentally the only resolution the monochrome monitor operated at. This resolution attracted business and publishing use allowing the ST to walk tall in the Macintosh’s arena. The ST was so well optimisted that you could even emulate Mac software at a faster rate than it ran on the base Apple hardware.

The second was those MIDI ports which immediately thrust the ST into the world of music, providing musicians a low cost and effective route into the sequencing and recording world, but we’ll get onto that in more detail later on.

The third trick, given GEMs roots of MS-DOS compatibility was that the ST could read and write MS-DOS formatted disks. A trick the Amiga would never be able to master.

Combined with the STs high performance base specifications, the machine proved to be truly versatile in a number of situations, both in home and professional use, and this led to over 50,000 machines being sold in the first 6 months alone on both sides on the Atlantic. At this time Tramiel made the company public and shares began to sell for triple their original price in just a few months. The ST had truly saved Atari from the dustcart in an amazingly short space of time.

To bring Atari’s old 8 bit line into synchronisation, the XE series was also launched this year, giving the older 800XL hardware a pleasing ST like aesthetic. This provided a more cohesive and unified range of products designed to show the company had progressed into another era of development.

Specifications

That’s 1985 out of the way, so, before we jump into 1986, let’s look at the specifications of this revolutionary machine;

Designed by Ira Velinksy, Look wise the original 520ST is a compact design, but that’s mainly because the power supply and floppy drive are external. Still it looks much more like the later home suited versions that incorporated these external blocks under the hood, whereas the original Amiga 1000 looks much more like an IBM PC setup, with base unit housing the floppy and separate keyboard.

On the back of the ST we find a multitude of ports from left to right;

- A reset button

- Power switch

- Power connector

- MIDI out

- MIDI in

- 13 pin DIN Monitor Port

- Centronics printer port

- RS-232C Serial Port

- 14 pin floppy port

- An ASCI DMA Port, for hard drives and other high speed peripherals.

On the left side we have a 40 ping cartridge port for 128kb ROM cartridges, whilst over on the right we have the mouse and joystick connectors. The ST shipped with it’s iconic wedge shaped mouse.

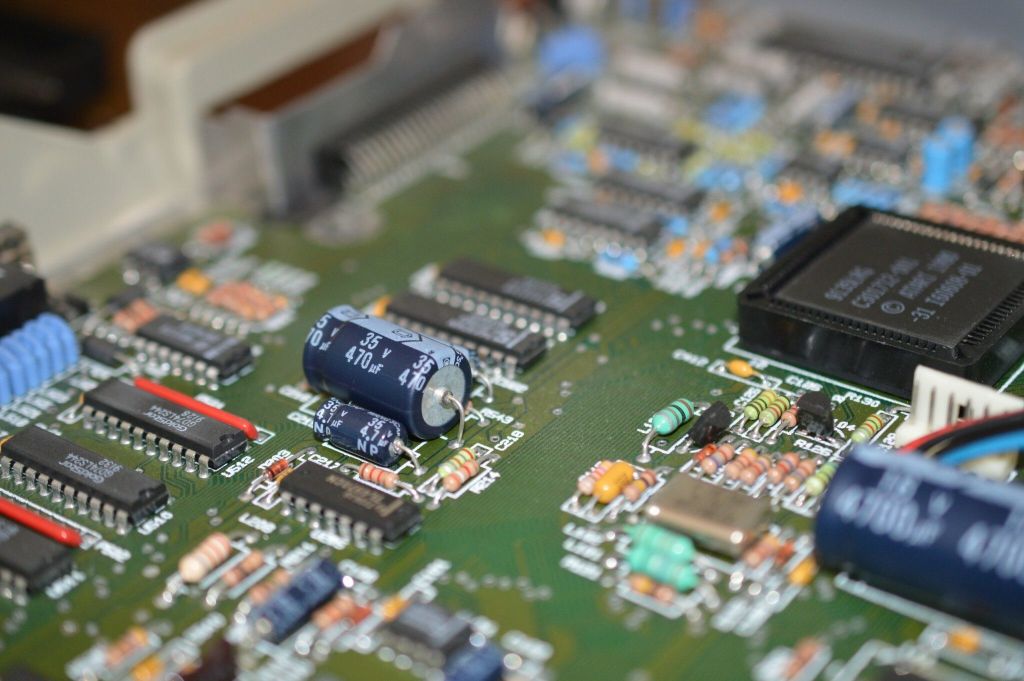

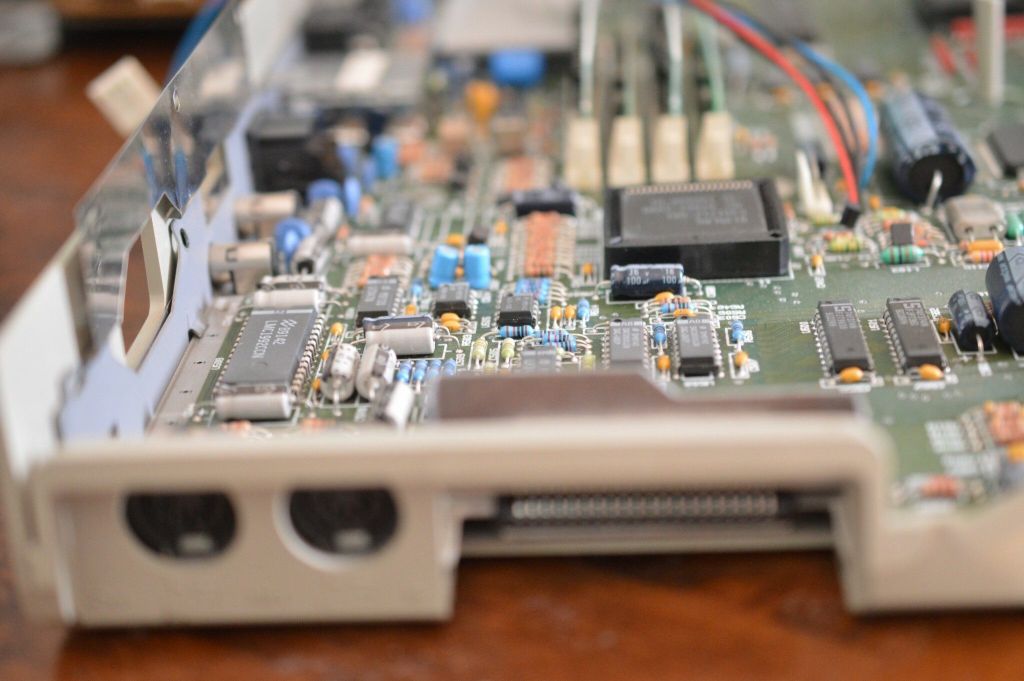

Underneath that slanted top grill we find the power of the ST. This comes in the guise of;

- That Motorola 68000 CPU clocked at 8MHz

- 512KB of RAM

- The Yamaha YM2149 sound chip capable of 3 voice squarewaves plus 1 voice white noise

- The display chip capable of a low resolution 320×200 at 16 colours, medium resolution of 640×200 at 4 colours and high resolution momochrome mode of 640×400.

- The palette is 512 colours

- The ST also has various custom chips from the Memory Management Unit to the Video shift register, which squeeze a high level of performance out of the commercial components.

The external floppy was originally single sided, capable of storing up to 360kb, with later drives up to double sided 720kb.

I find it very hard to talk about the ST without bringing the Amiga also in the equation, but technically they’re broadly similar. The ST’s 68000 is clocked almost 1MHz quicker, but the Amiga has custom chips which provided hardware scrolling, sprite support and advanced sound capabilities, all of which the base ST hardware lacked. I kind of see the ST as the Sinclair Spectrum compared to the Commodore 64 in the Amiga. Like the Amiga, the 64 had better hardware capabilities, but the Spectrum had higher resolution, a faster processor and a whole heap of quirkiness.

Post Launch

As 1986 came around, the ST kept selling, although many blamed Jack Tramiel’s harsh reputation on not selling more machines. Tramiel had often been critisised for treating retailers like competitors, rather than encouraging sales. This meant that large chains like ComputerLand or BusinessLand were not persuaded to stock Atari’s new machine. It was also noted that Atari’s erratic distribution plan of shifting between mass merchandisers to specialty computer stores didn’t help availability and dented retail confidence.

These issues also seemed to limit the number of software producers willing to publish on the machine, especially with the IBM and Commodore 64 markets seen as safe ground. But still, Atari managed to turn around their reputation and slowly, producers starting writing for the machine more and more with companies like Spinnaker and Lifetree Software switching to the ST as their highest priority.

The advertising slogan over in the States was “America, We Built if for you”, whilst over in Europe “Power without the price” quickly caught on, and seemed to chime with UK consumers who were more used to the all in one style systems that the ST aesthetically aligned with. The lower price also worked much better over here with IBM compatibles simply seen as professional business machines against the tide of low cost home micros we’d become accustomed to. But arguably one of the stand out changes to the playing field was the release of Dungeon Master in 1986. Games had already been released for the ST, many by Atari themselves including Star Raiders, Missle Command and Asteroids, but Dungeon Master made the gaming community stand up and take some serious notice. The sprawling first person RPG oozed atmosphere and picked up a plethora of awards before influencing a line of copycat RPGs up until this very day.

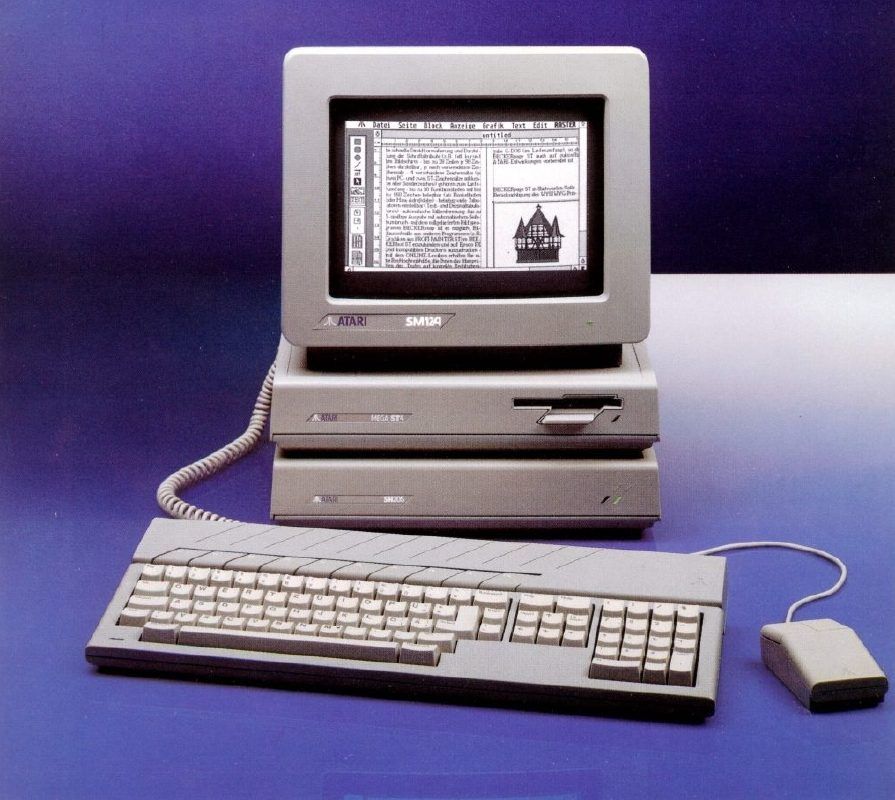

In 1986 Atari also launched some revisions to the ST line. The first was the 1040STF – a 1MB ST with a built in floppy drive and power supply. The 520M, feautring a TV modulator, but still an external floppy followed, quickly superseded by the 520STFM, effectively replacing the 520ST at the same time, incorporating a TV modulator, along with the power supply and floppy, allowing the machine to quickly enter the home markets in profound style. To accommodate the floppy drive, joystick and mouse ports were shifted to the somewhat awkward position underneath the unit; I mean, it looks quite neat, but it’s a pain which usually results in frantic wobbling and subsequent connection issues. The ST1, later renamed the Mega ST also debuted at Comdex, built in a style much more reminiscent of the Amiga 1000 and providing room for a 20MB Hard Drive upgrade. The Mega ST, along with Atari laser printer and the hard drive could actually be bought for less than an IBM laser printer by itself, quickly making it a very attractive option for Desktop publishers and graphic artists alike, especially with professional packages like Calamus and 1st Word Plus quickly arriving on the scene.

The ST had successfully infiltrated numerous markets. But it’s arguably the music and games markets where the most headway was made.

Let’s start with games.

Over in Europe, particularly the UK and France, the STFM was heavily marketed as a games machine. Along with the Amiga, it was one of the most advanced machines for gaming in this era. This was no more evident than with the Power Pack that bundled with every computer shipped from 1989 onwards. The Power Pack featured 20 of the most popular games for the ST, offering staggering value for money on a machine which already significantly undercut it’s competitors. Stand out titles on this gigantic disk collection include;

- Gauntlet 2

- Afterburner

- Starglider

- Bomb jack

- Predator and Super Hang-On to name a few

And the inclusion certainly outgunned the offerings of any other gaming machine at the time. The Discovery Pack was one of the best sellers featuring Jean Claud Van Dam in the advertising and box art, initially retailing for £299 over in the UK. In fact the marketing was so good that Atari were selling 75% of their computers in Europe. So, you might expect that things were looking rosy, but even though the Powerpack had been a mighty success, it was also in part, the machine’s downfall. You see, supplied with so many games from the go, owners of the ST felt less need to go out and buy further software. I mean, games were still selling, just not at the rate they had done in the past. To combat this, many producers jumped ship and started developing directly for the Amiga which was beginning to gain more support than the ST, thanks to the launch of the Amiga 500 in 1987. So whereas before, many development houses would produce a game on the ST, then port it over to the Amiga. Games started being written directly on the Amiga, taking advantage of the Amiga’s hardware. Because of this, the process of porting back to the Atari became a lot more arduous, leading to many titles just not being released on the ST format.

To try and combat the Amiga’s additional grunt, the STE was released in late 1989, in both 1MB and 520KB versions. The E stood for enhanced and featured;

- An increased colour palette of 4,096;

- Genlcok support;

- A blitter chip, providing advanced sprite and graphics support;

- 2 channel digital sound, with PCM 8 bit sampling;

- 2 enhanced joystick ports, located, pleasingly on the left hand side (these are actually compatible with Atari Jaguar pads)

- and SIMM memory modules to allow easier RAM upgrades.

It’s evident from the spec, that it was aimed at competing with Amiga. However, as with most upgrades, developers continued to mainly produce for the original ST machines or the Amiga, where the bulk of the customers lay. That’s not to say there weren’t games which took advantage of the STE, there were, as I knew all too well, as I flicked through Atari Format and found game upon game which required a fancy STE over my my humble STFM, but on the whole they were still few and far between.

Many high regarded individuals developed for the ST including Peter Molyneux, Doug Bell, Jeff Minter, along with numerous demo scene coders who regularly took up the task of proving that anything the Amiga could do, the ST could do better, and I mean, the ST could do some pretty fancy stuff when pushed, with some ST games even beating it’s Amiga counterpart. But there was also a lot of feeling among publishers that software piracy was rife and impacting their sales. Anyone who has heard of the Medway Boys should be familiar with dubious labelled disks cramming various commercial games somehow onto a single floppy. This apparently seemed less of an issue on the Amiga, with Amiga versions of games selling twice as many as the Atari format in the first few weeks of release. There were even pirate Bulletin board systems distributing software for free, which seemingly wasn’t as rife for the Amiga, and definitely wasn’t a problem on the consoles. This was another reason publishers jumped to other formats. But conversely popular programs such as GFA BASIC, FaST BASIC & STOS created a large community of homebrew and start-up coders who produced some impressive games for the machine, especially in the latter part of it’s life.

Other machines such as the Mega STE and Atari TT were also launched to squeeze into the professional markets, and replace the earlier Mega models. The TT is the higher end of these featuring the 32MHz Motorola 68030 processor, but it was met with limited success.

Despite all this, there was one area that the ST would excel in from the go and is still used for to this day….

MUSIC

Most people assume that the ST’s sound chip must be amazing, but the Yamaha AY chip is actually pretty modest. In fact, it’s very similar to the sound chip found in the Sinclair Spectrum 128k models, and the Amiga will nearly always blow it out of the water in chip tune standoffs. The real power of the ST as a music machine comes in the form of those MIDI connectors we spoke about earlier.

It wasn’t long after the machine’s launch that people realised the scope of the computer as a MIDI machine. Programs like Cubase, Notator & Logic Pro arrived on the scene. Allowing MIDI instruments to be recorded, arranged and edited with ease. Because the ports were hardwired from the go, the ST had very low latency response times, even compared to more expensive professional equipment, leading to a multitude of musicians making use of the equipment, including;

- The Utah Saints;

- 808 State;

- Fatboy Slim;

- Jean Michel Jarre;

- Madonna;

- and White Town’s “Your Woman” which burst out of nowhere in the mid 90s, and was produced almost entirely on the ST by some chap in his bedroom. It remained at #1 for several weeks.

Even to this day, the ST is used by musicians for editing, recording studio and even live use, including the grammy award winning Syro by Aphex Twin.

The End Times

Along with the machines already discussed, there were other spin offs like the STacy, a portable version of the ST released in 1989, powered by C cell flashlights and with a battery life of approximately 20 minutes. Upon realising this, Atari simply glued the battery compartment shut and sold the machine as a compact desktop. But at $2,299 it was a bit too much to swallow, selling 35,000 units in it’s lifetime.

There was also the ST Book, a laptop version of the ST without a backlight or indeed, a floppy drive. It was designed to take flash memory for storage instead, but released in 1991 only sold just over 1,000 units before being discontinued.

The 4160STE, featuring 4MB of RAM was never released, but badges were sent to dealers so that upgraded 1040STE models could be shipped under the 4160 moniker. These are incredibly rare to come by now days, but you can always get a label printed for yourself.

In 1992 Atari produced the Falcon, a follow up to the ST, which was rushed through development so quickly that it’s case wasn’t ready, leading to the coloured ST case we see here. Performance wise, the Falcon is a pretty mean machine, beating the Amiga 1200 on almost all of it’s specifications. Based on the Motorola 68030 running at 16MHz, sporting a Digital Signal Processor and bundled with a new improved MultiTOS operating system, it was a large step up from the ST, but by this point Motorola had lost the CPU battle to Intel and even their higher end chips like the 68040 just couldn’t keep up with the power and price of IBM compatibles. This is ultimately the downfall of all of these machines, whether it be Amiga or Atari.

Atari discontinued the Falcon and the ST in 1993, shifting to focus entirely on their new 64 Bit Jaguar console, but due to difficult architecture and the promise of powerful CD-based 3D consoles on the horizon in the guise of the Playstation and Sega Saturn. Publisher support was lacking and Atari ceased manufacture in 1996, with the company merging with hardrive manufacturer JTS inc. shortly after. Little was done with the Atari name until it was sold to Hasbro and finally Infogrames in 2001, where the branding is used to develop and shift software, including the recent RollerCoaster Tycoon World.

Amiga machines managed to hold on a little longer, with the hardware and third party support edge they had accrued in earlier years. The Amiga 1200 was discontinued in 1996 after brief relaunch from Commodore’s new owners, Escom.

The ST was never as big a success in America as it was in Europe, but then neither was the Amiga. It could be argued that both companies spent too long chasing the US market when they could have poured that resource into dominating Europe. But, whatever you want to attribute to the demise of the ST, it’s a similar story for most machines from this era. The IBM Compatibles simply got better, cheaper and started sweeping the market up. One by one, these unique variants of computer history disappeared, making way for a more beige, if compatible market of desktop machines. In many ways, that’s a good thing. Games can be tweaked to run on one platform. We can share files without worrying about compatibility, and ultimately prices are reduced due to increased supply and demand. But there’s definitely something missing from that last era of uniqueness. Of competitiveness. The era that started in the early 80s with the first 8 bits and finished in the mid 90s as Amigas and Ataris were shifted from main stream use and left as a remnant for hobbyists, the continuing demo scene and dedicated fans.

The excitement is gone. Maybe it’s just the nostalgia, maybe it’s because we were younger, but I think mainly, it’s because of the buzz these machines incited, through competition and their individual quirks. These machines forged discussions, arguments and indeed, friendships, from the playground to the workplace, just as they continue to do today.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.

3 Comments

Add Yours →One of the best articles I’ve read regarding the ST. I thoroughly enjoyed it. On Filfre.net there is a very similar more in depth article covering the same subject matter titled “The 68000 Wars” which is also a good read. Look forward to more articles. Harley Gerdes

The ST is the BEST 16 computer.

Hey there. I really enjoyed reading your article on the Atari ST. It brought back so many memories, but also nostalgia. I used to be a proud owner of the 1040STFM, bought in 1987 in Greece. I loved it to pieces and carried on using it until the mid-90s, when I could no longer find any new software. I have owned many home computers, starting with an Amstrad CPC464 and currently using an Alienware Beast of a laptop. None of them have given me as much joy as the Atari did, and I have never ‘bonded’ with any of them as I did with the ST. Yes, the Amiga owners would always smugly point out that they enjoyed better sound and graphics; but the ST owners were ‘salt of the earth’ regular guys, while the Amiga boys were pampered spoilt brats… Anyway – thanks for the memories. Dimitrios