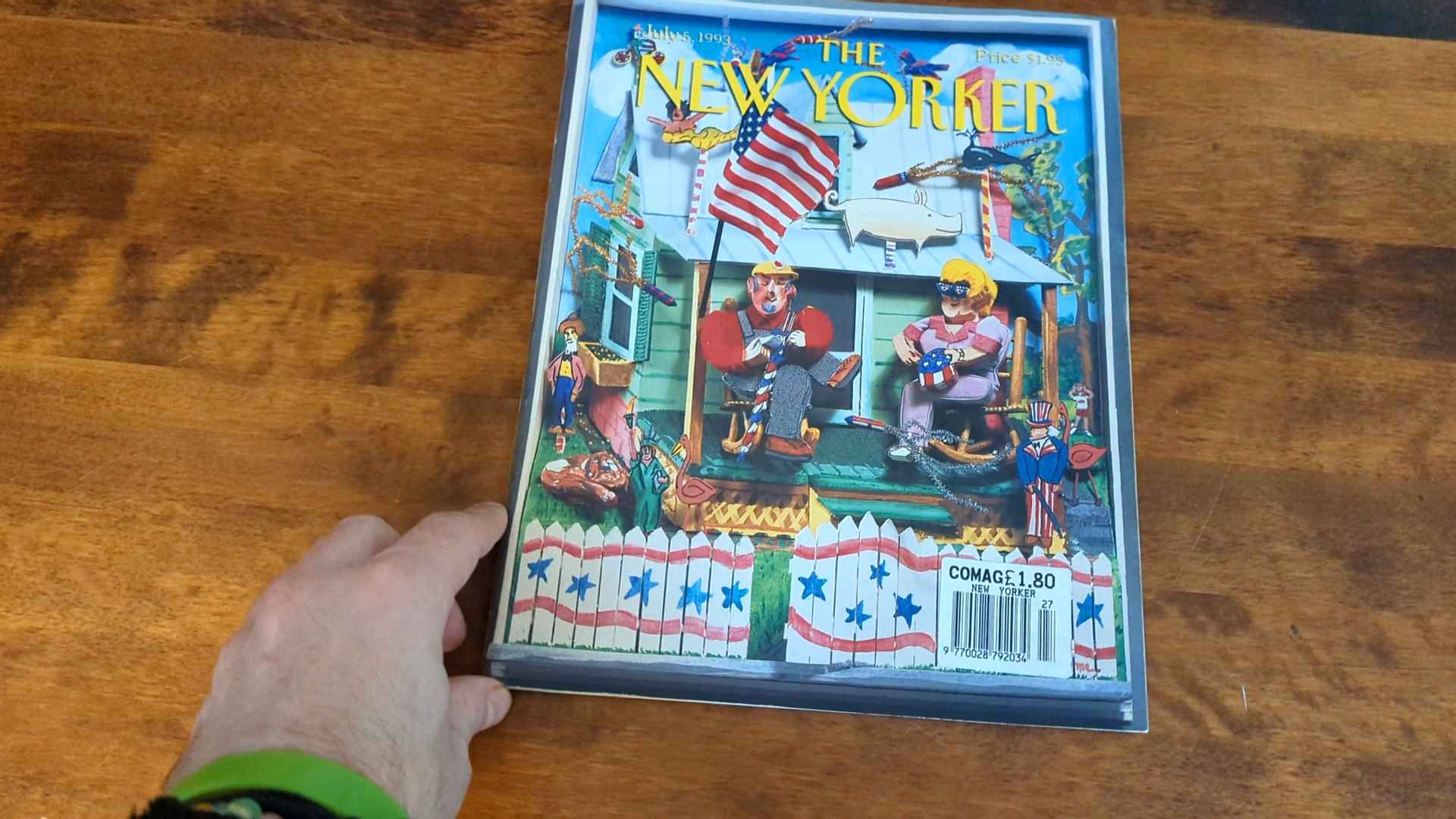

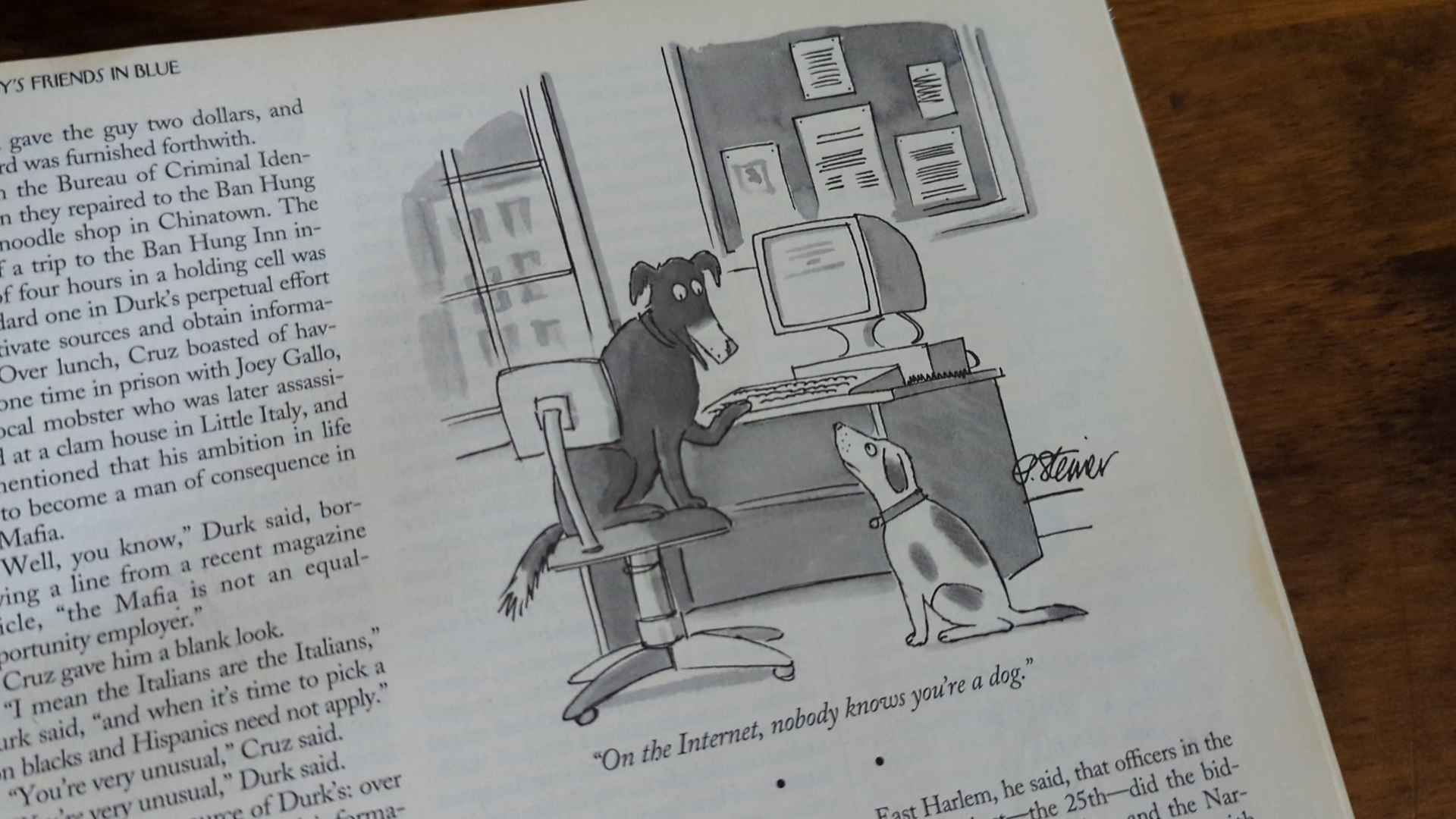

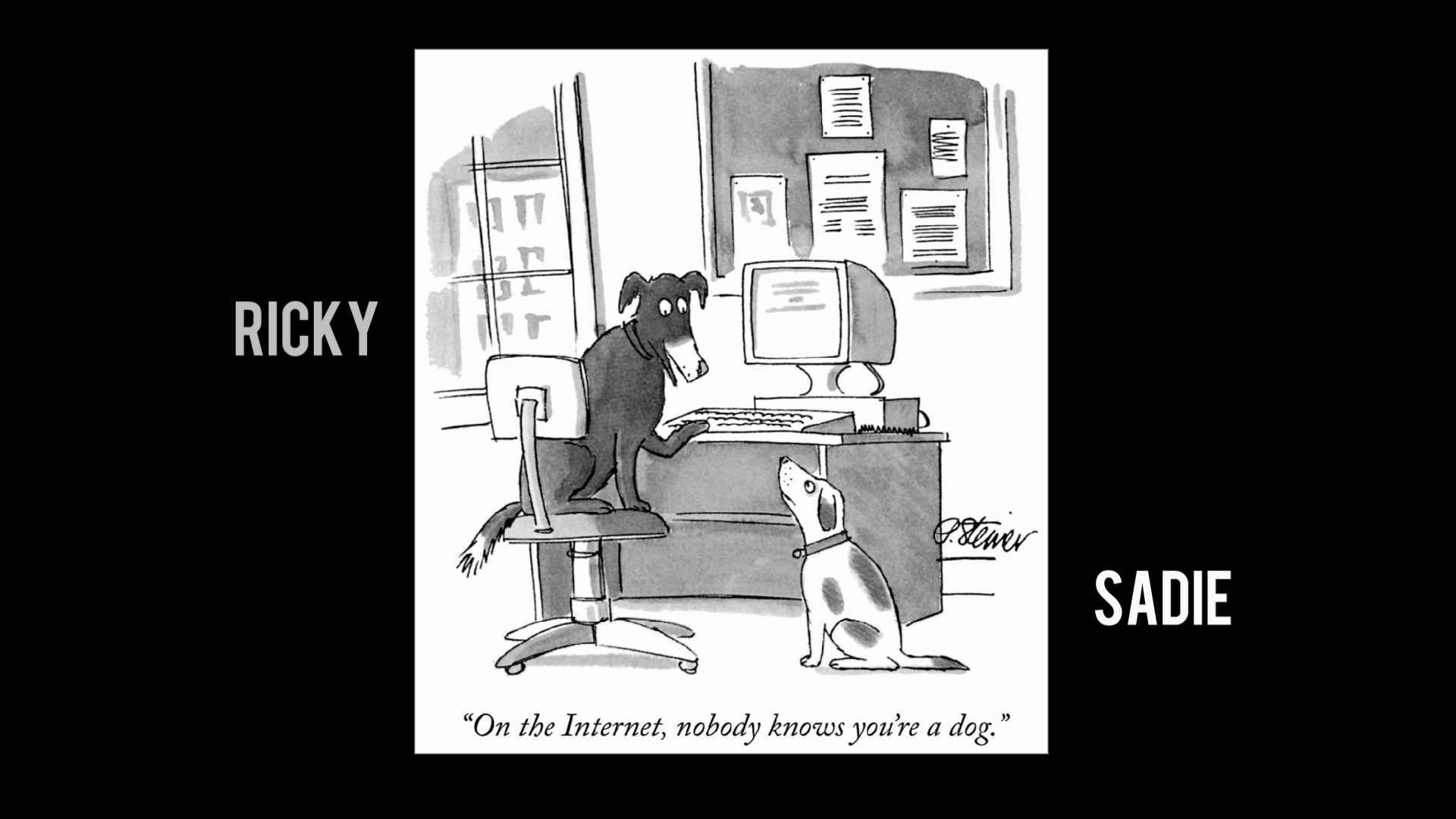

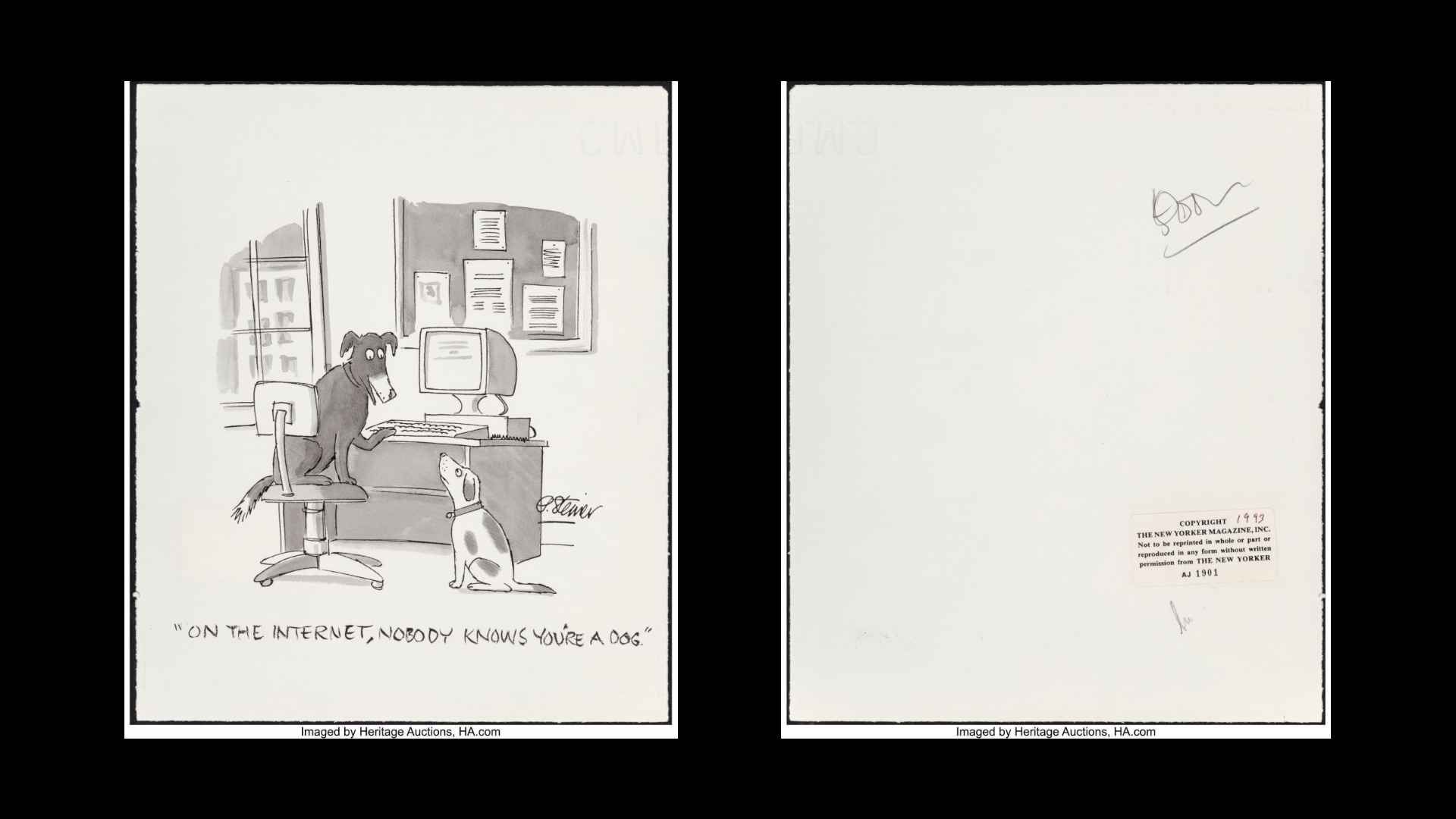

This is The New Yorker magazine, dated 5th July 1993. It’s significant because of a cartoon, drawn by Peter Steiner. Where is it. Ah yes, here we are page 61.

“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”

Nestled amongst a story about police corruption, this cartoon would become one of the most iconic in the world.

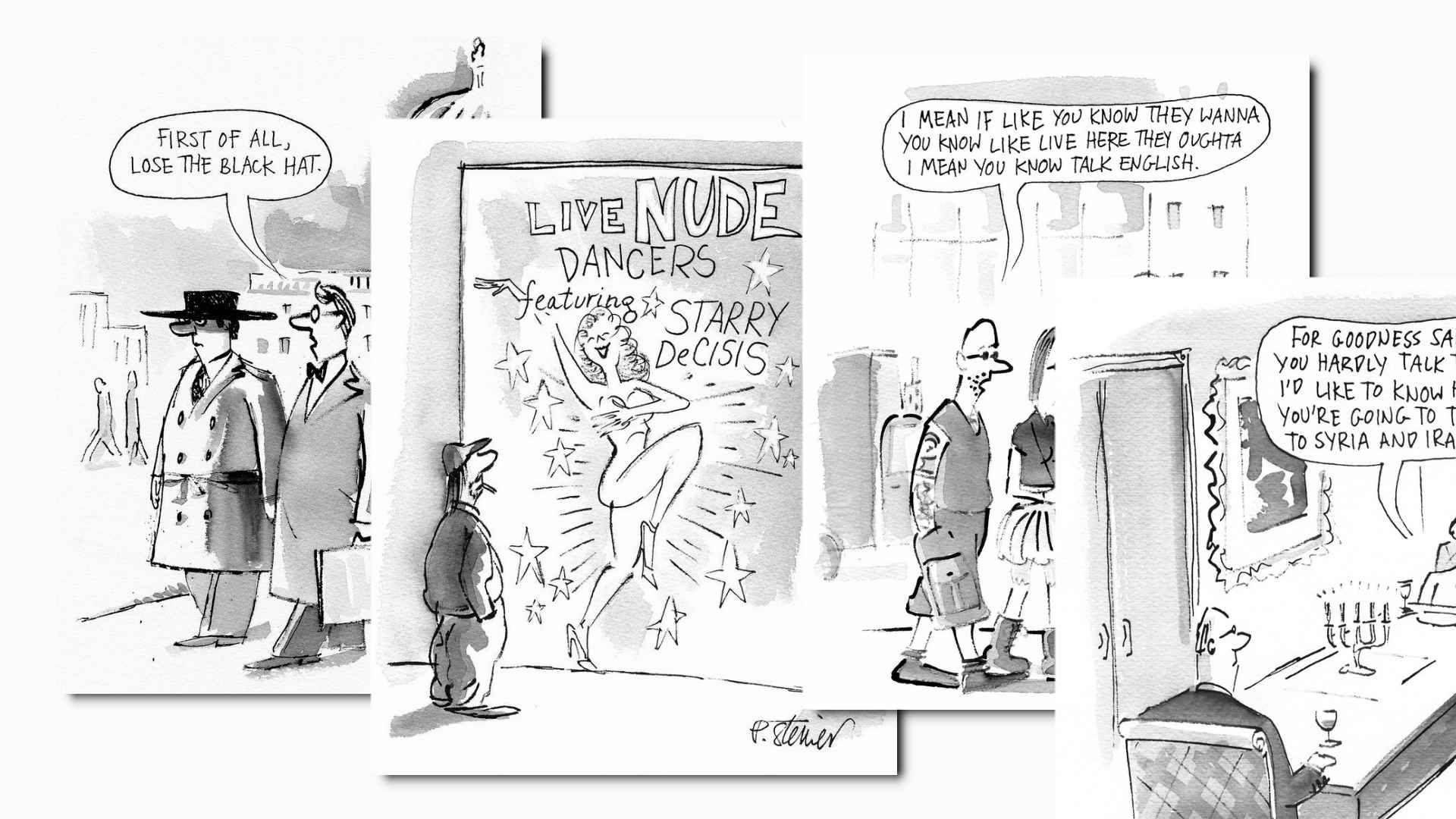

Back in these days, cartoonists would produce portfolios of panels, then walk from Collier’s to the Saturday Evening Post, and then to the New Yorker, meeting each editor to see if they wanted to purchase the artwork.

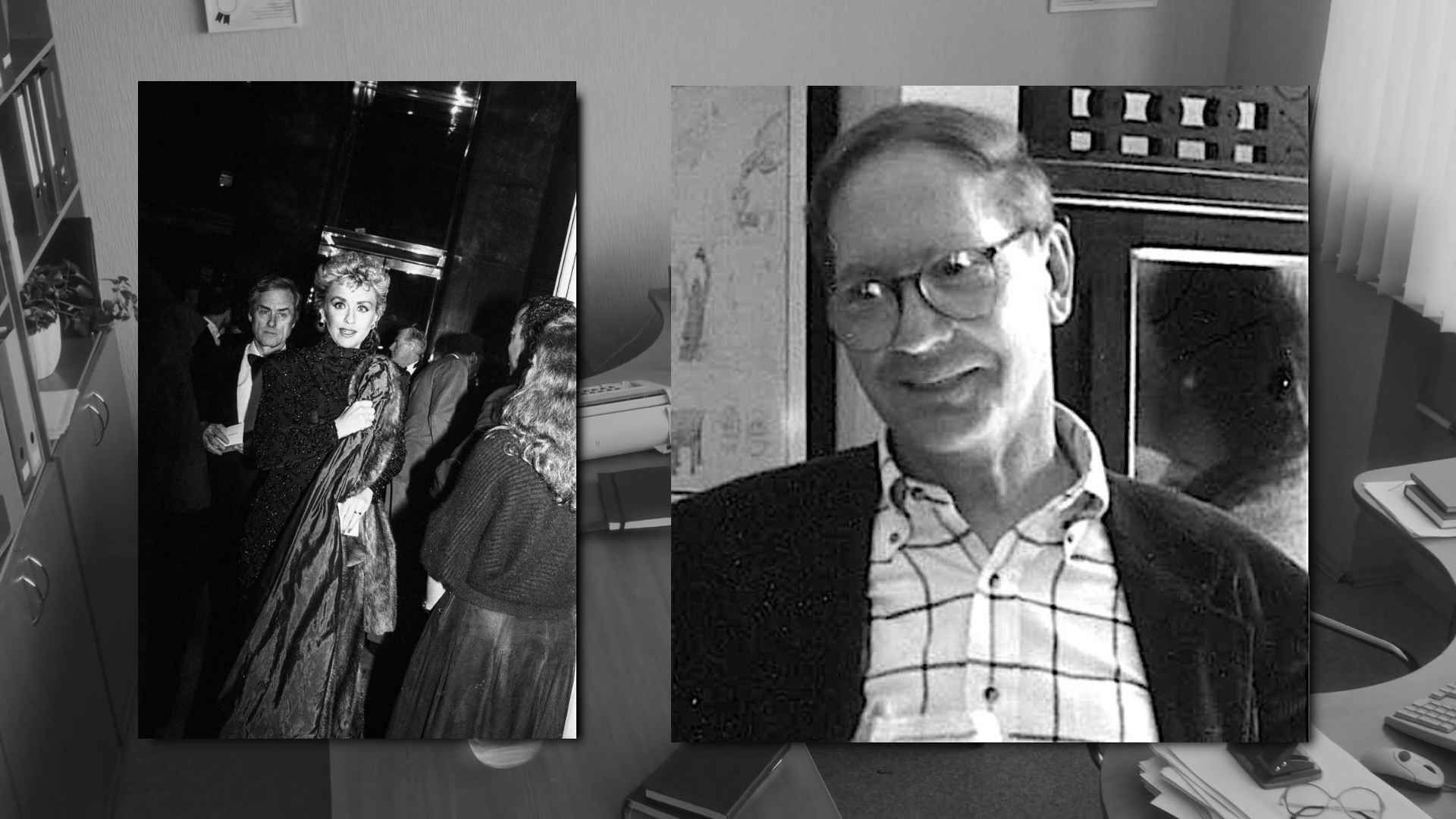

On this occasion, in the Summer of 1993, the then editor in chief, a Brit; Tina Brown;1 along with cartoon editor Lee Lorenz, felt this cartoon was perfect. For Steiner, it was actually a throwaway cartoon, and has since admitted to having no real interest in the internet at the time. It was simply a “make-up-a-caption” item to which he attached no “profound” meaning. In fact, with most people even unaware of the internet themselves, at the time, being mainly used for academic use, the cartoon didn’t make much of am impact upon its publishing at all. But then the magazine was routinely filled with cartoons, it was rare for one to have any kind of profound impact on society. But as time went on, it became a significant talking point, and perhaps one of the first and indeed greatest memes of our time…..

Peter Steiner

Peter Steiner was born in 1940 in Cincinnati, Ohio. He attended the University of Miami, earning a B.A. IN QUALIFICATION, before serving in the US Army and earning an MA and Ph.D in German literature from the University of Pittsburgh. He then went on to become a professor of German literature at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania for eight years before becoming a cartoonist, artist and novelist.

On his own website, Steiner writes that when he was five or six, he found a copy of his parent’s book, The Lonely Ones by William Steig and was mesmerised2, setting him out on a path that would always lead to this career.

He joined The New Yorker in 1979, and then the Washington Times in 1983, creating daily cartoons relevant to the news at the time. All of Steiner’s cartoons had a particular type of witty humour that helped shine a light on contemporary matters in a more whimsical light than the editorial sections might.

Of course, with the rise of the internet in the 90s, and the World Wide Web infiltrating households in 1993, Steiner felt he had something to say. He’d actually produced various cartoons on the subject of computers, but “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” struck a chord, and although it wasn’t instant, the wider media began to use the catchphrase within only a matter of months.

Spreading the MEME

The first copy I can find of the cartoon being duplicated was actually in the same month. On the 20th July 1993, various syndicated publications, including Newsday printed the picture alongside an “Information Highway” article, where a report hitches a ride on said highway; essentially giving the lowdown on where technology has been and where it’s headed.

From there, it would pop up in various other articles discussing this new highway of information and opportunity. For a while it was seemingly used as an introduction of sorts;

“Surely you’ve heard of the internet. Almost certainly you had not hard of it a year ago. In that span, it has gone from unheralded region of cyberspace to topical and stylish locale, the kind of place that shows up in a New Yorker cartoon: A canine hacker says “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”3

A light hearted, whimsical way to lure in the technophobes.

On 6th December, Time Magazine ran an article on the “First Nation in Cyberspace”, talking about how the internet was making waves globally. But on the 2nd page of that article it said;

“‘It’s the Internet boom’, says network activist Mitch Kapor, who thinks the true sign that popular interest has reached critical mass came this summer when the New Yorker printed a cartoon showing two computer-savvy canines with the caption, ‘On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.'”

There had been plenty of other prominent cartoons about the internet, but this one really seemed to capture the mood at the time. This mention in Time magazine, by the founder of Lotus Software, seemingly caused the cartoon to spread everywhere else. It was an ignition moment.

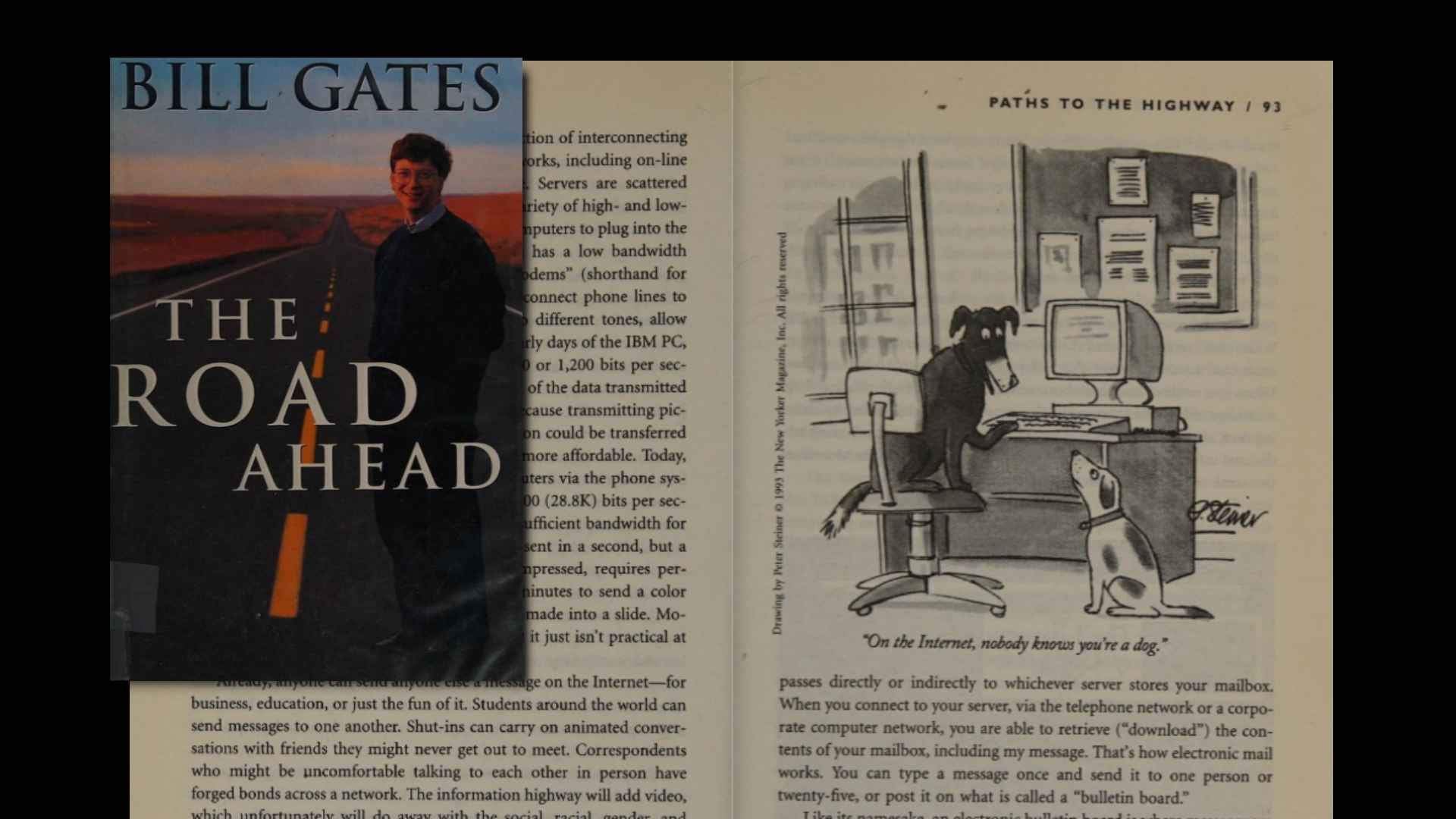

and this didn’t let up the following year, or the following year, or the next. It was even featured on page 93 of Bill Gate’s book, The Road Ahead, This phrase, and this imagery had apparently encapsulated this new technology. But the question is, why?

The 2000 Interview

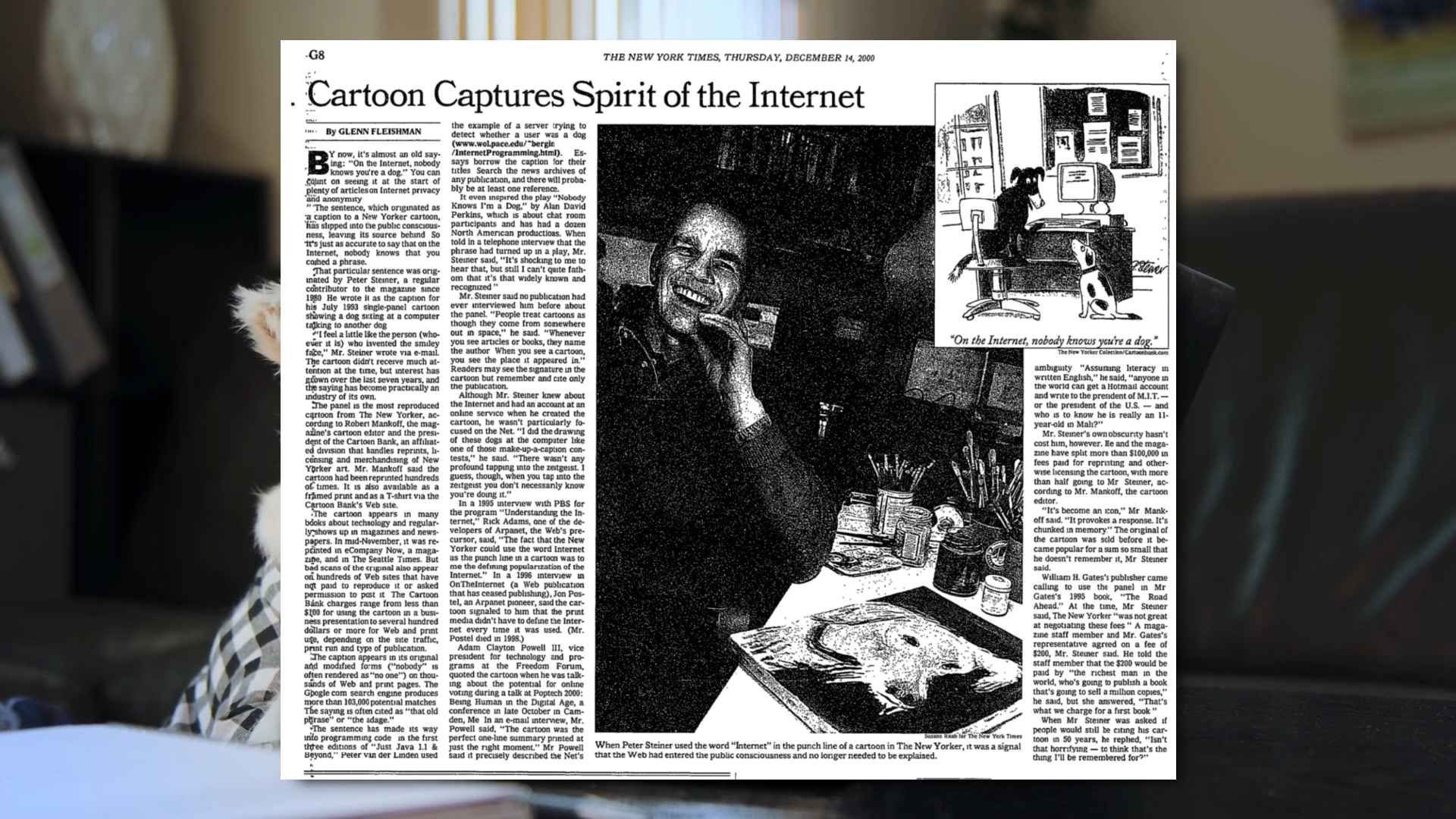

On 14th December 2000, the New York Times ran an article titled “Cartoon Captures Spirit of the Internet”4. The article starts “By now, it’s almost an old saying: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” You can count on seeing it at the start of plenty of articles on Internet privacy and anonymity.

By this point, 7 years on, people had a better grasp on the internet and the cartoon was now used more appropriately regarding trust issues around the web. But this article, by Glenn Fleishman, was actually an interview with Peter Steiner himself, in a quest to find out deep this rabbit hole goes.

“I feel a little like the person who invented the smiley face” quips Steiner… “The cartoon didn’t receive much attention at the time, but interest has grown over the last seven years and the saying has become practically an industry of its own”

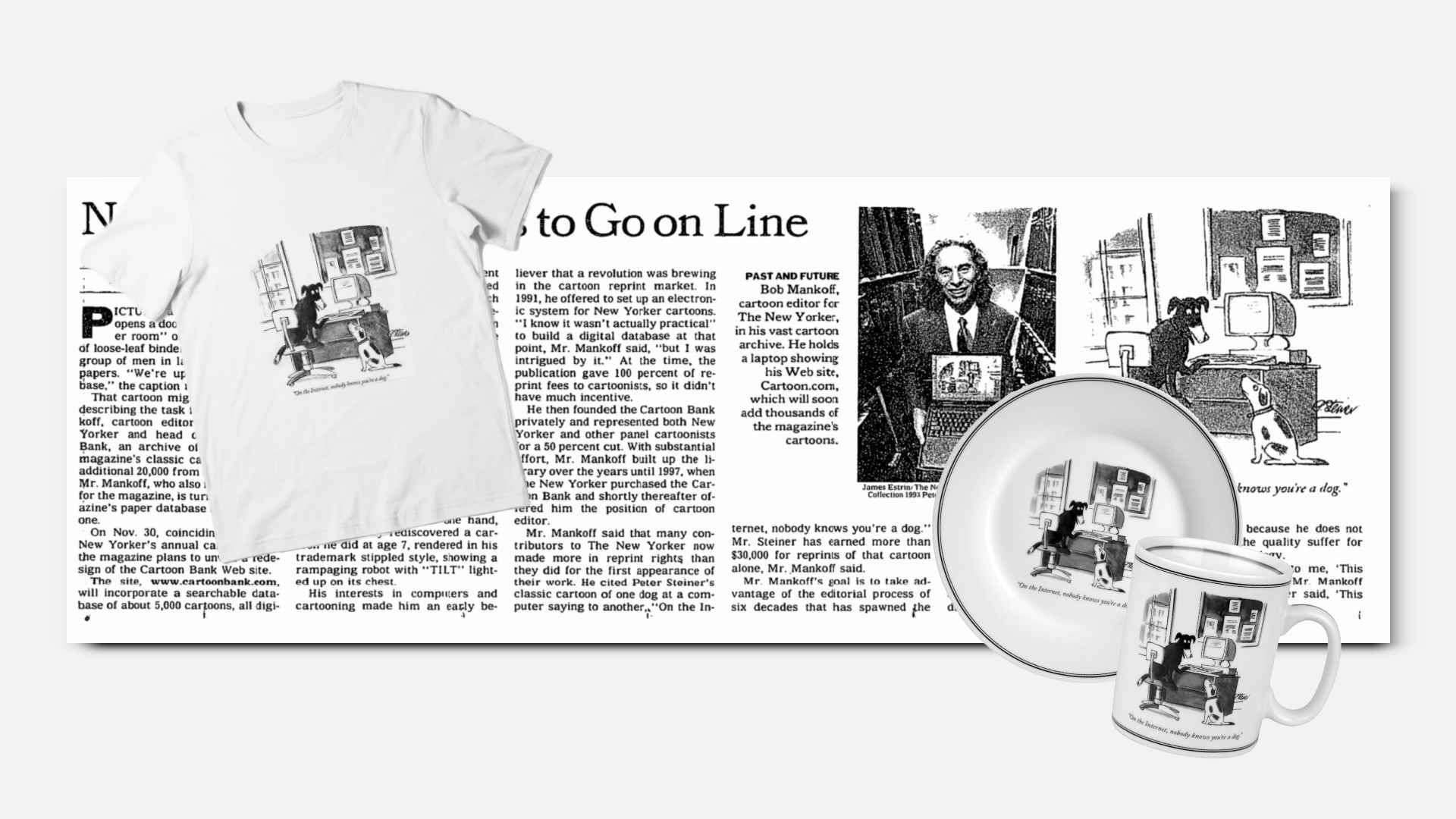

In fact, at that time, the cartoon was the most reproduced from The New Yorker, and was available on T-Shirts, in framed prints, among other merchandise. A quick search on Google yielded 103,000 matches, and it was working its way into Java programming examples. This simple “dog server” attempts to detect whether you are indeed, a dog.5

In fact, by this point, it had even inspired a play “Nobody Knows I’m a Dog”, by Alan David Perkins. A story about chat room participants who were all pretending to be something they’re not.6

The cartoon had certainly struck a chord and whether Steiner intended it or not, people were extracting their own meaning.

This, simple, throwaway cartoon wasn’t just striking a chord with our fears. The fact that anyone could be lurking on this new communication network, striking up conversations with your family, your friends, your children, and pretending to be someone they’re not.

It was also providing a means of liberation. In a world filled with assumptions, stigmas and stereotypes, you could rock up and be whoever you wanted to be. This didn’t mean that you could simply redefine yourself, it also meant that you were free to perform the boldest action of them all; simply being yourself, in your truest form.

People were discovering internet anonymity.

The Greater Media

A study completed in the year 2000, by Morahan-Martin and Schumacher7 on compulsive or troublesome Internet use discusses this phenomenon, suggesting the ability to represent one’s self behind the mask of a computer screen may be part of the compulsion to go online.[13] The phrase may be taken “to mean that cyberspace will be liberatory because gender, race, age, looks, or even ‘dogness’ are potentially absent or alternatively fabricated or exaggerated with unchecked creative license for a multitude of purposes both legal and illegal”.

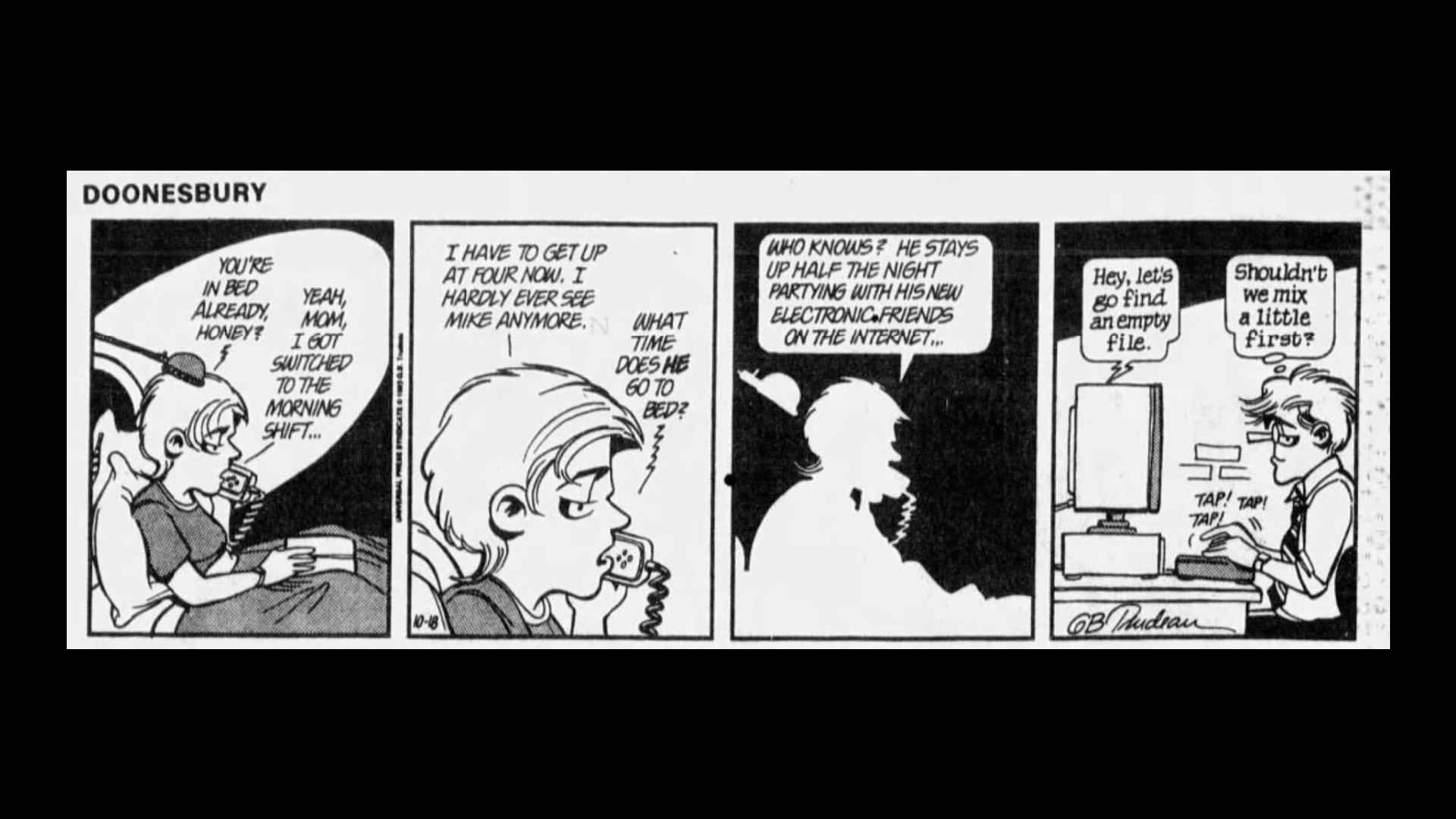

This was also portrayed in media at the time. Films such as You’ve Got Mail, where the main characters fall in love through the anonymity of the internet, or The Net, where Sandra Bullock goes on the run from an unknown enemy after stumbling across government secrets, conveys both the excitement and fear of this new technology.

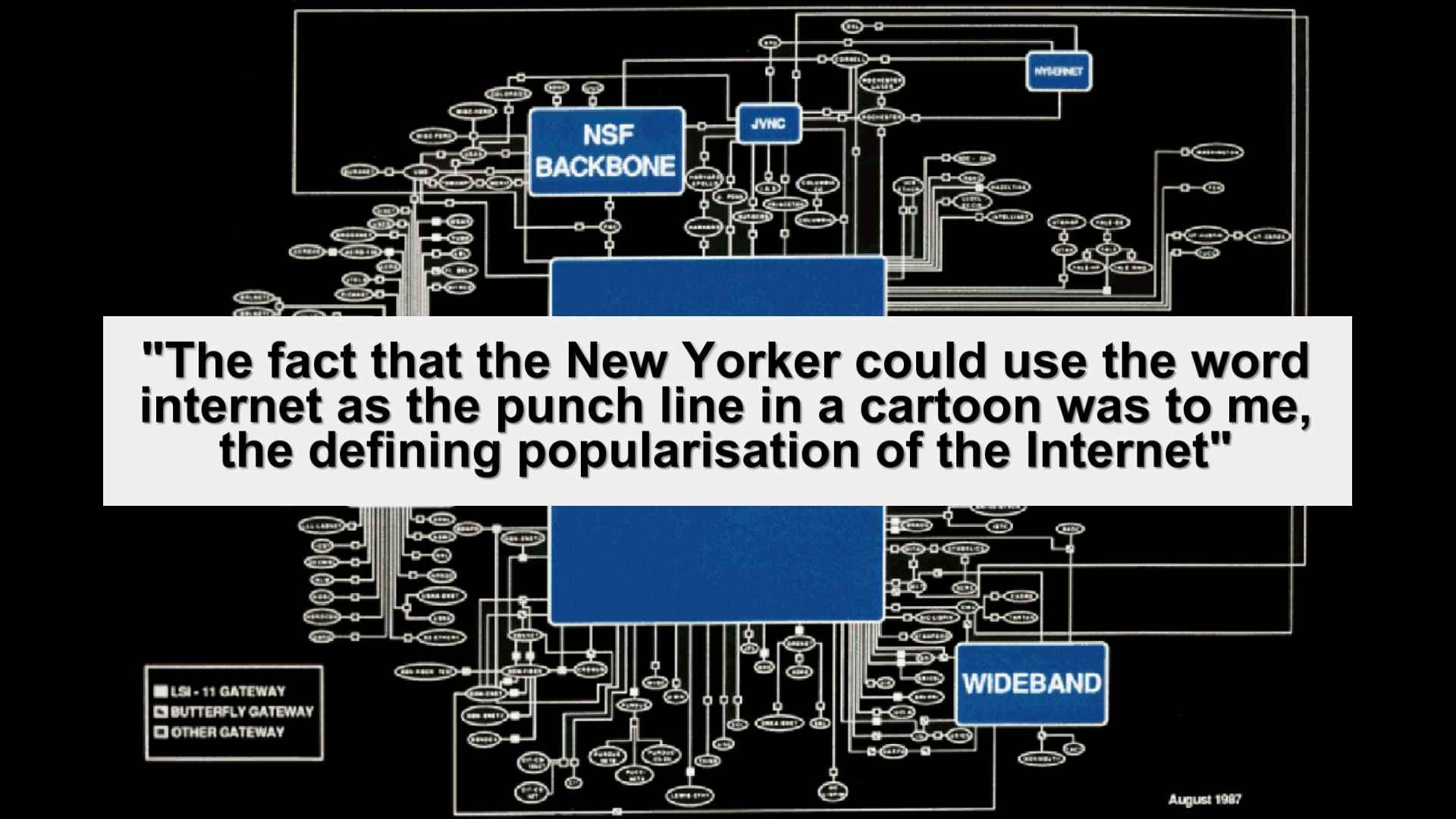

What Peter Steiner did, was manage to capture all of this, in a single frame, before the vast majority of people were even aware of what the internet was, and for this reason it’s absolutely priceless. In a 1995 interview with PBS, Rick Adams, one of the developers of the web’s precursor, Arpanet stated “The fact that the New Yorker could use the word internet as the punch line in a cartoon was to me, the defining popularisation of the Internet”.

It’s probably no coincidence that Steiner almost seemed to draw comparisons between his career and the internet; “People treat cartoons as though they come from somewhere out in space…. Whenever you see articles or books, they name the author. When you see a cartoon, you see the place it appeared in…. Readers may see the signature in the cartoon, but remember and cite only the publication”. Something only proved by Rick Adams earlier statement.

For Steiner, and for so many other creatives, his work was almost as anonymous as random people on the internet, and maybe that’s also why, when it came to the internet, he was ahead of the curve, even though he wasn’t particularly interested in it at all….

“I did the drawing of these dogs at the computer like one of those make-up-a-caption contests” “There wasn’t any profound tapping into the zeitgiest. I guess, though, when you tap into the zeitgeist, you don’t necessarily know you’re doing it”

“By now, it’s almost an old saying: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”. The sentence which originated as a caption to a New Yorker cartoon, has slipped in to the public consciousness, leaving its source behind. So it’s just as accurate to say that on the Internet, nobody knows that you coined a phrase”

And this is true even today. Famous Memes. Famous sayings. Famous posts, are all copied, and pasted, without any reference to the original source. What’s more, no one really cares what the original source was.

The Cartoon is Updated

In 2012, Steiner would update the cartoon with a segment for the New Yorker’s Cartoons of the Year 2012 Collection.8 In this spread, he not only named the dogs, Ricky and Sadie, with Sadie being the one who actually came up with the phrase. He also created an entire life for them, which sadly ended in their parting of ways.

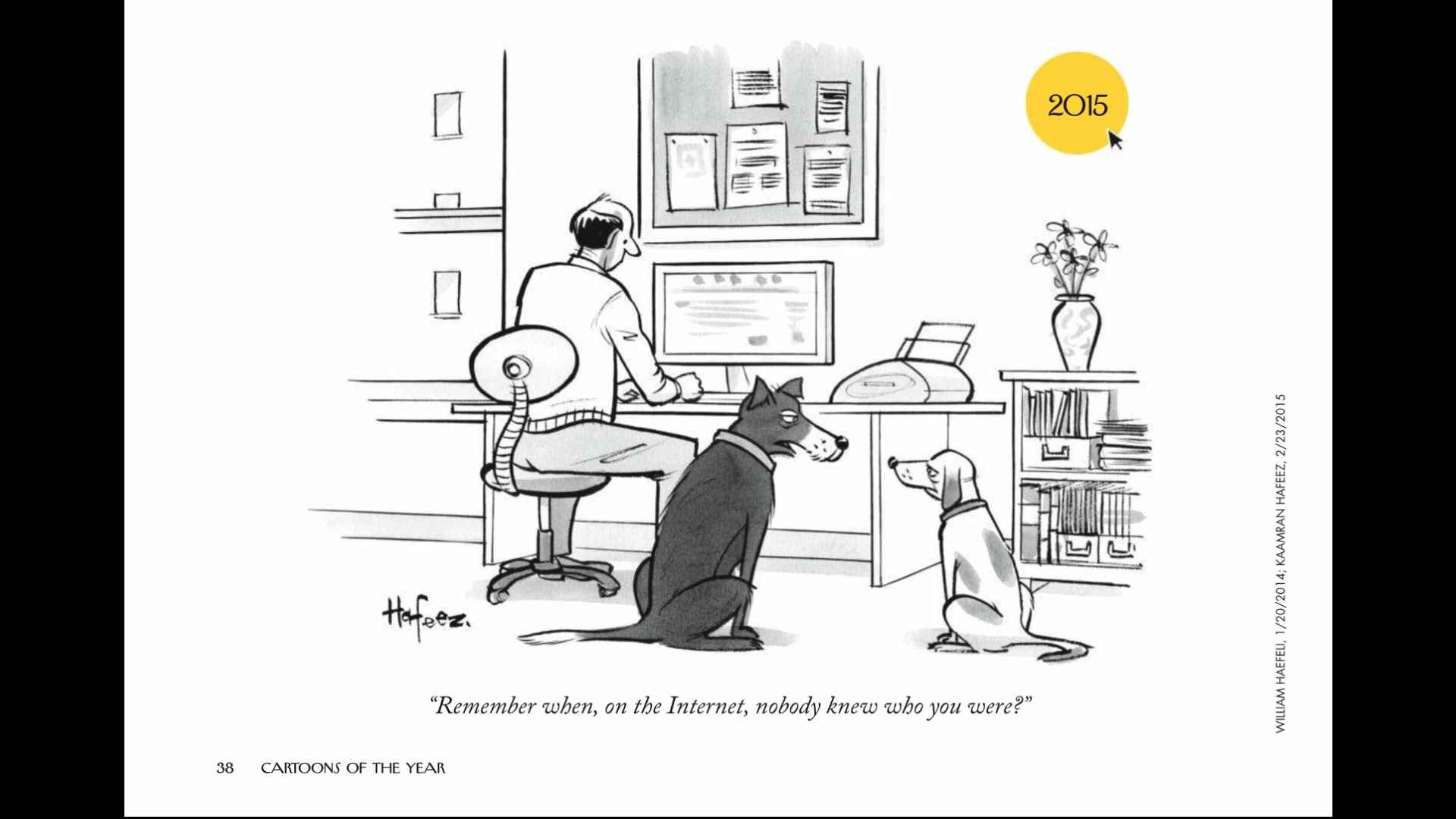

In the Cartoons of the Year 2015, the New Yorker published “An Incomplete History of the Internet” which started with the famous dogs, and also ended with a new pair, illustrated by Kaamran Hafeez, and capturing the changes that had occurred in the preceding 22 years.

“Remember when, on the Internet, nobody knew who you were?”

Internet Privacy

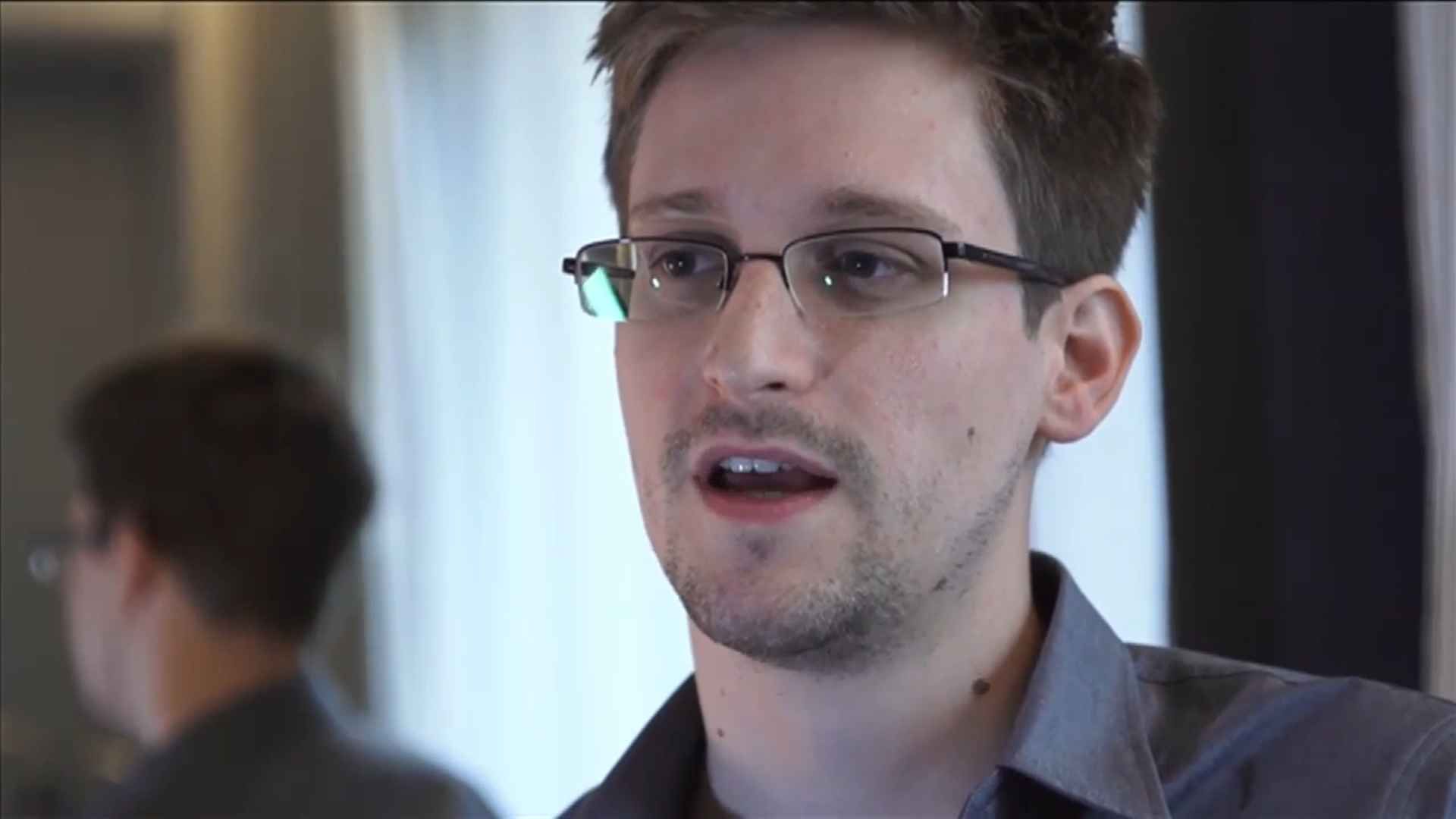

This wasn’t long after Edward Snowden exposed information that left debates over mass surveillance, government secrecy and just how complicit private enterprise is in exchanging our data with our governments9. In 22 years, we had gone from an internet where anyone could log on, and be anyone, with not even the ISPs being able to track who was doing what, to an internet where, sure you could create a random email account, and setup anonymous social media accounts, but your data, your movements, were almost certainly being tracked somehow and somewhere.

In some cases, On the internet nobody knows you’re a dog, is still very true, but, some server, somewhere, definitely knows you are not a dog. It knows your name is Peter Leigh, it knows you live in Norwich and it knows that you have a cat called Spencer.

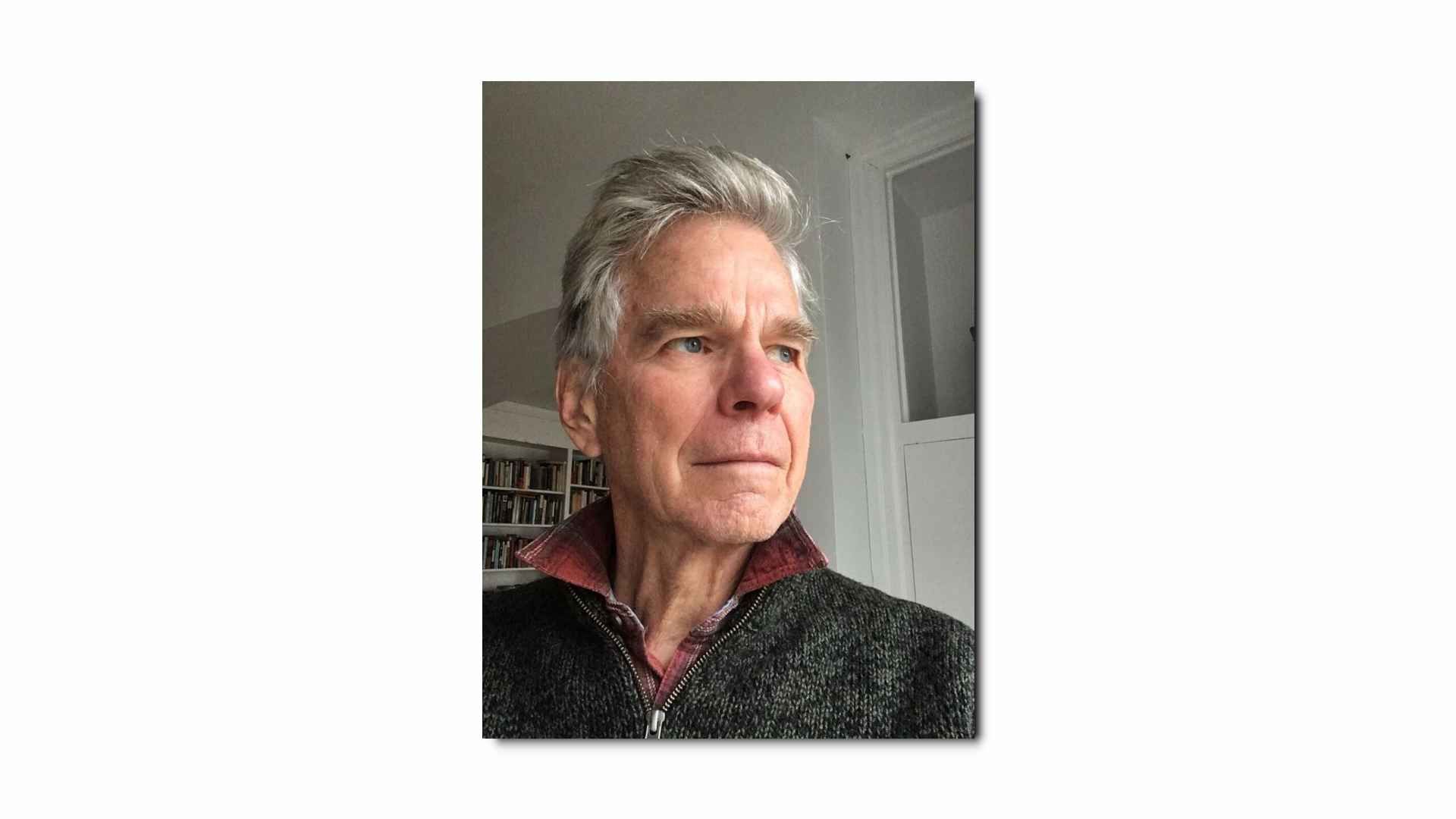

In 2013, Glenn Fleishman, then editor and publisher of The Magazine updated his interview with Peter Steiner.10 By this point Steiner had moved away from creating cartoons, focussing on writing novels, including various crime mysteries.((web.archive.org/web/20121127154026/http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/cartoonists/2012/10/peter-steiner-novelist.html))

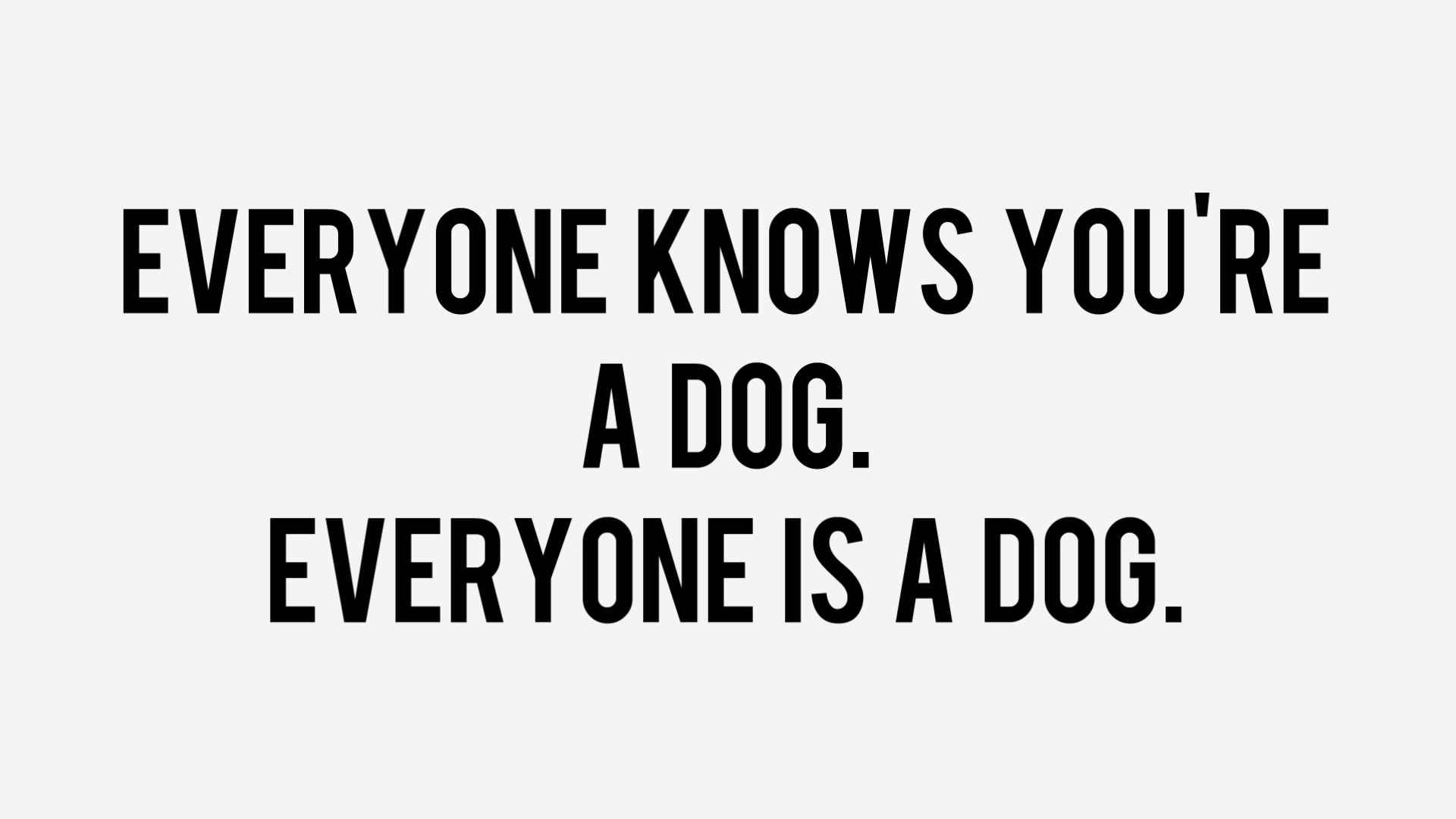

But even at this point, he was well aware of the tinge the cartoon had taken, summing it up like this;

“Everyone knows you’re a dog; everyone is a dog”.

What about now?

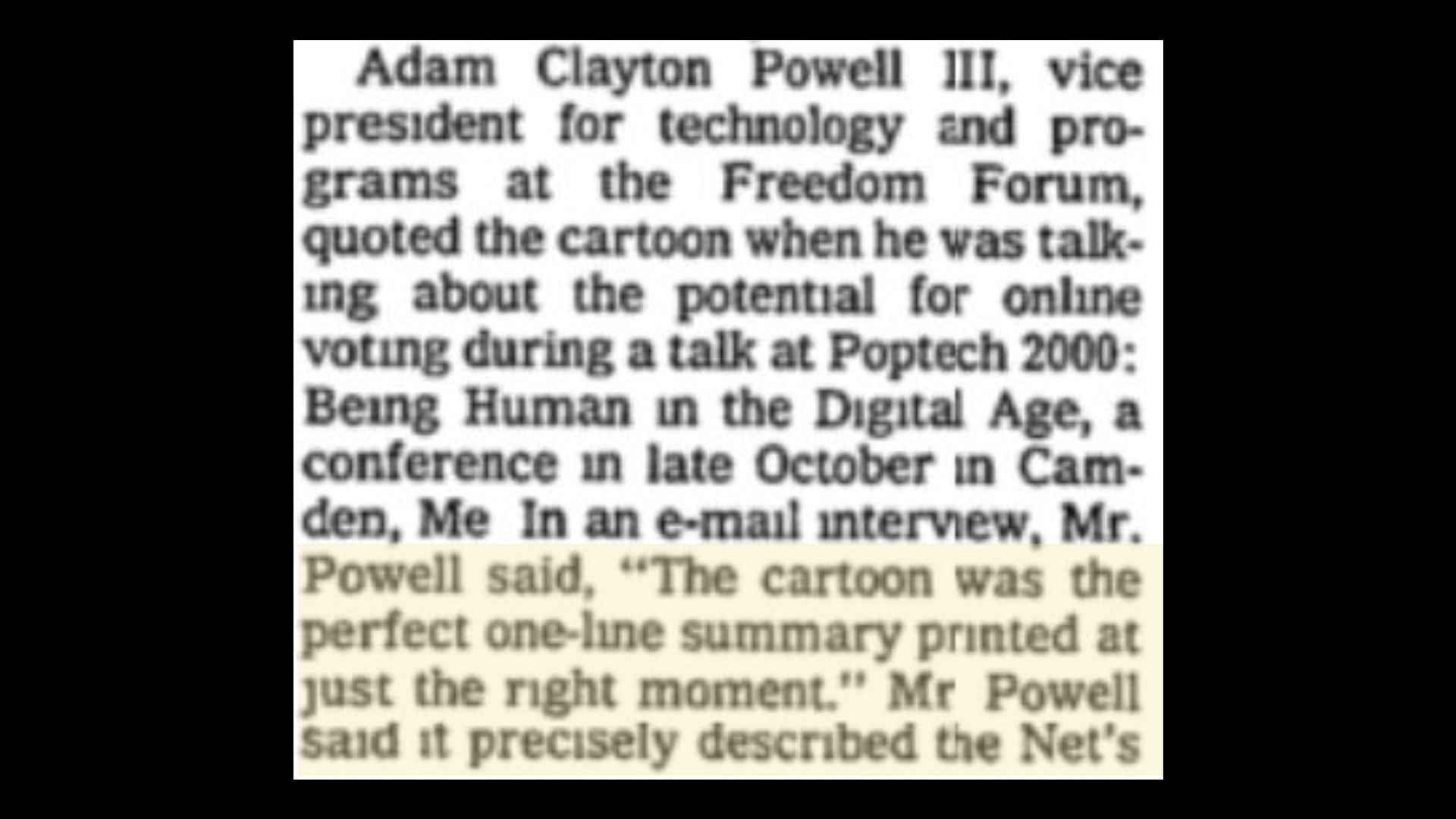

Since the cartoon was first published, he estimates he had probably received around $250,000 in royalties,11 receiving a 50/50 split with New Yorker, which sure, it’s a lot, but remember this is spread out over two decades. The New Yorker actually accepted 421 cartoons from Steiner over the years, but none made as much impact as this one. As Adam Clayon Powell III, Vice president for technology at the Freedom forum in New York Times quoted “The cartoon was the perfect one line summary printed at just the right moment”.12

The original signed artwork though, despite originally being sold by The New Yorker for a few hundred dollars, went on to become one of the most famous cartoons ever. Hardly surprising then that is sold for $175,000 at a Heritage Auctions sale on 6th October 2023, which included a online conversion with Peter Steiner beforehand.13141516

Steiner: “I realised that the cartoon is autographical, and it’s about being an imposter or feeling an imposter. It wasn’t about the internet at all. It was about, that I was getting away with something”

Pretty crazy that after 30 years, Steiner would finally realise that the cartoon was in fact simply about having imposter syndrome.

Bob Mankoff: “What were you getting away with?”

Peter Steiner: “Well being a cartoonist for one thing. I’ve had several checkered careers, and in every one I felt like a bit of a fraud. I think many people have syndrome.”

Something that many of us can definitely relate to. Especially in the creative field.

Back in 2000, when the New York Times asked Steiner if people would still be citing his cartoon in 50 years, he replied “Isn’t that horrifying – to think that’s the one thing I’ll be remembered for”.

But it’s not just being remembered or a cartoon. It’s being remembered for symbol that is even more important to the web today, as it was back then. Our freedoms, our internet privacy is continually at stake, and it has helped sparked many debates and conversations since.

Plus, it’s art. Everyone who sees it will interpret something different, even it it is just a cartoon. A $175,000 cartoon.

I always find it wild that most of the people I know who suffer from imposter syndrome, are actually the most talented people I’ve ever met. Goes to show, if you feel like am imposter, just keep going.

Until next time, I’ve been Nostalgia Nerd, Toodleoo.

Toodleoo.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.

- www.britannica.com/topic/The-New-Yorker [↩]

- www.plsteiner.com/cartoons [↩]

- www.newspapers.com/image/464857304/ [↩]

- timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/2000/12/14/issue.html [↩]

- web.archive.org/web/20021214145702/www.wol.pace.edu/~bergin/InternetProgramming.html [↩]

- www.backstage.com/magazine/article/nobody-knows-dog-1-40565/ [↩]

- www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563299000497?via%3Dihub [↩]

- michaelmaslin.com/new-yorker-cartoons-year-2012/ [↩]

- www.theguardian.com/world/video/2013/jul/08/edward-snowden-video-interview [↩]

- the-magazine.org/21/everybody-knows-you-re-a-dog/index.html [↩]

- web.archive.org/web/20190328013315/https://boingboing.net/2013/10/17/everybody-knows-youre-a-do.html [↩]

- www.nytimes.com/2000/12/14/technology/cartoon-captures-spirit-of-the-internet.html [↩]

- www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/the-most-reprinted-new-yorker-cartoon-breaks-record-at-auction-for-a-single-panel-comic-180983135/ [↩]

- attemptedbloggery.blogspot.com/2023/09/peter-steiner-on-internet-nobody-knows.html [↩]

- news.artnet.com/market/new-yorker-cartoon-highest-price-auction-2381602 [↩]

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZeA8MFOudA [↩]